For many anglers, dry fly fishing represents the pinnacle of the sport. There are numerous reasons why topwater fishing is loved by so many. For starters, you can see the take of the fish and surface eats are often exciting. In warmwater environments, a fly floating on the surface can avoid fouling when fishing weed-filled waters, making it the only type of fly that you can use in some conditions. I love fishing dries and will do it whenever conditions are suitable for it. Nothing beats the sights and sounds of a big bluegill taking a fly on top!

Visually observing the strike takes a lot of guesswork out of hooking a fish but is not always that easy. Timing the strike, near misses, and refusals can still perplex anglers. Improper timing in setting the hook is probably the number one reason anglers miss topwater eats. You must resist the urge to set the hook the very second you see the take. Allow a second or two to pass before setting the hook. Your hook-up ratio will improve if you allow the fish to turn and head down with the fly before setting the hook. But wait too long and the fish will reject the fly and you are out of business. Over time you seem to develop a sixth sense in regards to how long to wait before setting the hook on a fish.

Whenever you are fishing a floating fly you should be ready to react to a hit the moment the fly hits the water. This means managing loose line at all times, as any slack will reduce your effectiveness in setting the hook. When setting the hook on fish like bluegills and other sunfish simply raising the rod tip will usually do the job. For tough-mouthed fish like largemouth bass, I will usually set the hook using a strip strike. Simply lifting the rod will not move the fly enough to penetrate the hard mouth. Instead of lifting the rod tip, you set the hook with a series of strips, with the rod tip pointed at the fish or simultaneously sweeping to the side.

The take of a fly off the water's surface can be an imperceptible sip, a violent explosion, or something in between the two. Any way they come, surface hits are exciting and will keep you coming back for more.

Bluegills of all sizes love to feed on the surface. Even smaller fish have no problem grabbing a beetle pattern.

Few fish share the bluegill's affinity to eat on the surface. This combination of fishing a dry fly and a fish that can't resist eating it is what makes fly fishing for panfish so enjoyable. But what fly should you choose? The fly fisher who chases panfish has a mind-numbing variety of flies to choose from. Traditional dry flies, hair bugs, poppers, and foam bugs will all work if the fish are looking up.

This deer hair pattern works well as a beetle imitation but it is hard to keep floating after it has been chewed on by a few fish. Tying with foam solves this problem.

Flies tied with foam offer some advantages over other materials. Keeping a dry fly floating, especially after catching a few fish, can be a problem. A properly constructed foam pattern goes a long way to solving this issue. In addition, cleaning off fish slime and re-applying floatant is usually unnecessary with foam flies.

While foam may not be the ideal material to tie a delicate mayfly or caddisfly, it does a fine job on many terrestrial patterns, particularly beetles. There are somewhere around 400,000 species of beetles crawling around on this planet. In addition, beetles constitute almost 40% of known insect life and 25% of all animal life! So chances are pretty good that a few are going to end up in the water and ultimately in a belly of a fish.

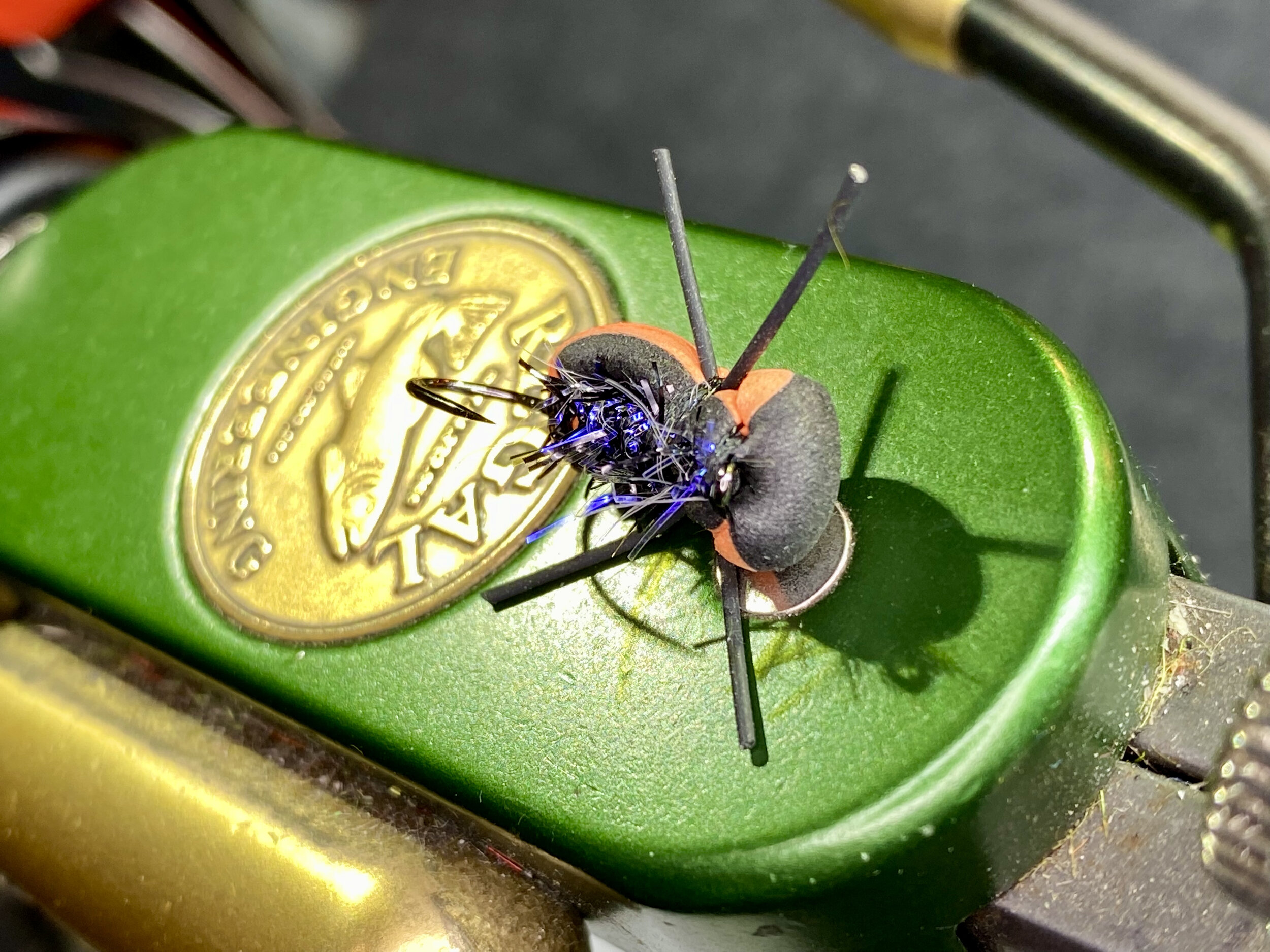

A simple foam beetle with a Straggle String underbody and rubber legs. The bright yellow disc of 1mm foam allows you to easily keep track of this dark flush floating fly.

There are many effective foam patterns for panfish, including my own Triangle Bug, but few flies can match a foam beetle's fish-catching charm. A foam beetle tied with a chunky body made from thick closed-cell foam lands on the water with a fish-attracting splat, just like the actual insect. If there is are any bluegills in the vicinity, they are unlikely to resist grabbing it.

Tying effective beetle patterns

Most beetle patterns are simple to tie. A simple but effective beetle imitation can be constructed by lashing a foam strip to a hook and doing nothing more. However, my love for fly tying compels me to do a little extra work. Adding an underbody, some legs, and maybe an indicator of hi-viz foam or yarn (to aid in finding the flush floating fly) usually does the trick for me.

I prefer to use a thicker foam for beetle patterns. Semperfli’s 4.5mm foam compresses well and is easy to work with.

I prefer to use a thicker foam for my beetle patterns. While 2mm foam is adequate for designs like the Triangle Bug, flies like beetle patterns benefit from a beefier body. I prefer to use foam like Hareline's 3mm, the 4.5mm foam from Semperfli, or bi-color laminated foam on my beetles. A laminated foam allows you to use thicker foam with two colors. One side to present to the fish and brighter color to allow the angler to see it clearly on the water. Regardless of which type you choose the thicker foam gives the flies that all-important splat when they hit the water and keeps them floating all day long without any assistance.

Using laminated foam allows you to present one color to this fish in this case a natural looking black and another color (hi-viz orange) to the angler. This makes for a very visible fly that has a natural underwater profile. The Semperfli Straggle String underbody adds a little movement and flash to the pattern.

To aid in compressing the thicker foam without cutting through it use heavier thread. I will not use anything lighter than 6/0 or 140 denier when working with foam. When compressing or tieing down the foam, start with light wraps and apply more pressure with each consecutive wrap. This will collapse the foam without cutting through it. This method is a useful technique, particularly when working with thicker foam.

You can keep your underbody simple (thread wraps can suffice), but I like to add a body of peacock herl, dubbing, Straggle String, or floating poly yarn under the foam shell of my beetle patterns. An underbody can add additional movement or a little flash to your fly, increasing its fish catching ability. While many of the beetles in my trout boxes are tied without legs, I can't resist adding legs to my beetle patterns that I will fish in warmwater. While you can find more complicated beetle patterns to tie, the simple design described at the end of this article is all you need to fool big bluegills.

Tips for fishing beetle patterns

Overhanging tree limbs are a prime place to fish a beetle pattern. In sunny conditions like this you will need to get your fly deep into the shade under the branches. Keeping your cast low and skipping the fly on the water’s surface will allow you to get back under low hanging branches.

My preferred method for fishing beetle patterns in warm water is to find a shoreline thick with overhanging trees, preferably shaded. I will then cast my beetle pattern back under the branches as far as I can. A chunky beetle pattern works well for a technique I call skip casting. A skip cast lets you bounce the fly off the water's surface and skip it back under cover; it is a valuable technique for fishing structures like overhanging trees and docks. You accomplish this by keeping your cast low and parallel to the surface of the water. I usually add a little haul on the forward casting stroke to accelerate the line and make the fly skip easier.

Big bluegills love beetle patterns but they will often inspect them for a while before committing. Fish your beetle with long pauses and don’t move the fly too much. Fishing a beetle pattern can be painfully slow.

Once the fly hits the water, let it sit for a while without disturbing it. Beetles are feeble swimmers and do not move much. The key is to animate the fly without dragging it across the surface of the water. You do this by applying very subtle twitches to your fly line. Keep your rod tip low to the water and keep as much line on the water as possible. By doing this, it can help you to keep moving the fly too aggressively. Allowing the fly to sit motionless is usually more effective than actively moving it. Rather than fishing the fly all the way back to you, pick up and present it again if a fish does not grab it after a few twitches.

As the sun sets and well into dark a beetle pattern fished over open water will often bring fish to the surface.

I have also found fishing a beetle pattern over open water at sundown or after dark an effective technique. Many species of beetles are nocturnal and become active as the sun sinks below the horizon. These clumsy fliers often head out over open water and end up in the drink. Having a big June Bug fly into your hair or down your shirt while fishing after dark while out in a boat or kayak emphasizes the fact that beetles spend time out over open water at night!

Beetles are a staple terrestrial pattern that works well in warm and cold water. If you don't have a few beetle patterns in panfish fly boxes, you are missing out on a tremendous topwater pattern. So tie some up and give them a try. You won't be disappointed.

Pattern Recipe:

Hook: Firehole 618 size 14-8 (the #618 is my go-to hook for many foam patterns)

Body: Sheet foam cut in a strip slightly wider than the hook gap of the hook you are using. Try 3mm, 4.5mm, or laminated foam for a thicker body that produces the all-important SPLAT!

Underbody: You have a few choices here. you can keep it simple with thread alone or add a body of dubbing, peacock herl, Straggle String/Straggle Legs, or Floating Poly Yarn.

Legs: Round rubber or silicon.

Indicator: Hi-vis 1mm foam